WHEN THE GAZE OF OTHERS BECOMES THE ONLY MEASURE OF WHO YOU ARE

When the belief of being judged by everyone meets an environment that confirms that judgment, the perfect bomb is born. And the only real failure is not allowing oneself to fail. – Marcello de Souza

She carries a certainty that no one ever planted with words, yet it grew all the same, the way the most powerful things grow—in silence, in repetition, in the atmosphere. The certainty is this: everyone is watching. Everyone is measuring. Everyone, at every moment, is forming an opinion about her—about what she did, what she didn’t do, how she did it, when she did it, whether she did it well enough.

It is not paranoia. It is not insecurity in the shallow sense of the word. It is something more sophisticated and, for that reason, more difficult to disarm. It is an entire system for reading the world that operates like this: every person around her is an evaluator. Every interaction is a test. Every delivery is an exam. And the result of that exam does not determine only the quality of the work—it determines the worth of the one who produced it. If the delivery is good, she is worthy. If the delivery fails, she fails. Not the project. Not the task. Her.

It is a brutal equation in its simplicity: I am what I deliver to the eyes of others.

And the most devastating part is that she does not know she is obeying this equation. She thinks she is merely “committed.” “Detail-oriented.” “Demanding of herself.” These are the beautiful names we give to a mechanism that, beneath the makeup, is pure fear. Fear of being seen as someone who fails. Not as someone who did something that failed—that would be tolerable, that would be human. But as someone who is failure. Who has a structural crack. Who, if others look closely enough, will notice that behind the competence lies a fragility she hides with the same zeal she uses to organize her spreadsheets.

Let us speak of this fragility. Because it is not what it seems.

When I say she does not accept being recognized for her failures, I am not saying she is arrogant. I am not saying she does not tolerate criticism. I am saying something deeper, more painful, and more human than that.

She does not accept failure because, in her internal system, failure is not an event—it is a sentence. It is not something that happened—it is something she is. There is an abyssal difference between “I made a mistake on this point” and “I am the kind of person who makes mistakes.” For most people, this difference is clear. For her, it does not exist. The error and the identity are fused. Welded together. Every failure—no matter how minor, how routine, how utterly common—is experienced as an exposure. As if someone had pulled back a curtain and revealed what she most fears others will see: that she is not perfect.

And the absurdity—the absurdity that hurts—is that her failures are exactly that: common. Normal. The kind of thing any competent professional commits and forgets the next day. A detail that slipped through. A piece of information that was missing. A deadline that got tight. Nothing that changes outcomes. Nothing that compromises the whole. Nothing any reasonable person would consider grave.

She is not any reasonable person when the subject is herself. She is, simultaneously, the defendant, the prosecutor, the judge, and the jury. And in this private tribunal, there is no acquittal for lack of evidence. There is only condemnation by accumulation of imperfections.

Now consider this: a person who lives like this—for whom every interaction is a test and every failure a sentence—placed in a work environment that does exactly what her belief predicts.

Because this is the central point: it is not a neutral environment misinterpreted by her. The environment is not neutral. It demands. The manager does not merely guide—he micromanages. Recognition is not distributed for invisible effort, but for easily measurable results.

There is, in fact, a structural asymmetry: while she sustains complex, innovative projects that demand time, maturation, and systemic intelligence, others handle smaller fronts, yet more visible, more marketable, and more quickly profitable.

She manages complexity. The system rewards apparent simplicity.

And it is exactly here that the silent conflict is born: whoever carries what does not appear almost never receives what should be recognized.

The environment did not create the belief. The belief was already there—formed in silence, over years, in other contexts, in other relationships. What the environment did was far worse: it confirmed the belief. It gave her concrete evidence. It transformed what was an internal hypothesis—“everyone is evaluating me and will find me insufficient”—into a lived, daily experience, documented in emails and silences.

This is the perfect bomb.

On one side, an internal structure that says: my value depends on how others see me. On the other, an external context that says: indeed, we are watching, and what we see does not impress us enough. The belief provides the fuel. The environment lights the match. And the explosion is silent—it happens inside, without anyone around noticing, because she is exactly the kind of person who maintains composure while collapsing.

I need to pause here and say something that may disturb.

She cares about others. Genuinely. This is real. It is one of the most beautiful things about her—this attention to what the people around her need, feel, think. But there is a twist in this care that turns it from a quality into a trap.

Because when she “cares about what others think,” she is not exercising empathy. She is exercising vigilance. She is scanning the environment all the time—the manager’s tone of voice, the colleague’s expression, the time someone took to reply to an email, the silence in a meeting—searching for signals. Signals of approval or disapproval. Signals that she is safe or that the ground is about to give way.

Empathy is caring about what the other feels. Vigilance is using what the other seems to feel as a thermometer of one’s own value. They are movements that look alike on the outside and are radically different on the inside. In empathy, the other is an end—she cares because she cares. In vigilance, the other is an instrument—she monitors because she needs the other’s reading to know if she is okay.

And this monitoring is exhausting. It is not an effort she makes occasionally, in moments of tension. It is a program that runs permanently, consuming energy, attention, and presence. It is like keeping a hundred tabs open in the browser: each tab is a person, each person a possible evaluation, each evaluation a possible condemnation. And she must monitor them all simultaneously, because if she misses one—if she does not notice that someone is dissatisfied, if she does not anticipate a criticism, if she does not foresee a disappointment—she will be caught off guard. And being caught off guard, for someone who lives like this, is equivalent to being caught unprotected.

The body pays the bill. It pays with insomnia. It pays with the jaw that locks on its own. It pays with shoulders that rise when the phone rings. It pays with that exhaustion that does not improve with rest, because it is not work fatigue—it is the fatigue of vigilance. Her nervous system operates as if there were a constant threat, and the threat is the gaze of the other. Against threats that live outside, we can run or fight. Against a threat that lives in one’s own perception, there is no escape. The danger travels along.

And relationships? This is the saddest and most important part.

A person who lives under constant vigilance of others’ gaze often becomes, without realizing it, less available for real relationships—not more. Because she is not fully present in the encounter. She is present in the management of the encounter. She is calculating: what to say, how to say it, what the other is thinking, whether that phrase sounded good, whether that silence means something.

And the other feels it. The people around her may not know how to name what they perceive, but they perceive: there is something contained, something that does not flow, something that seems care and attention, but that has a background of calculation. And slowly, without confrontation, without rupture, relationships lose spontaneity. They become efficient, correct, functional—and empty of a certain grace that only appears when no one is measuring anything.

This creates a perverse cycle. She strives so that others see her well. The effort makes interactions artificial. Artificiality generates distance. Distance is interpreted as… rejection. And rejection confirms the belief: I knew it, they do not approve of me. When, in truth, there was no rejection—there was discomfort with something the other cannot explain. It is like hugging someone while wearing armor: the intention is affection, but what arrives is cold metal.

She is not cold. She is the opposite of cold. She is too warm, too involved, too concerned—and it is precisely the “too much” that gets in the way, because the “too much” does not come from the heart. It comes from fear.

There is something that needs to be said about perfectionism, but not in the way it is usually said.

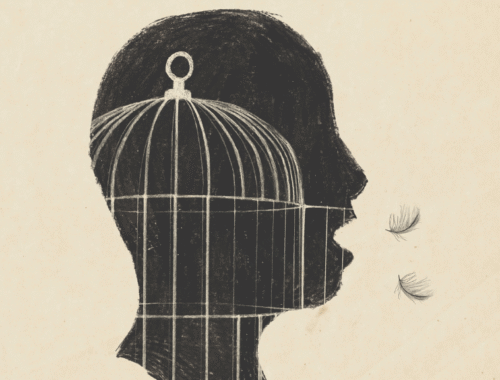

Her perfectionism is not vanity. It is not aesthetic obsession. It is not “wanting everything beautiful.” It is the last line of defense. It is the wall she built between herself and the world’s judgment. The logic, distilled to its essence, is this: if I am perfect, no one can criticize me. If no one can criticize me, no one will see my failure. If no one sees my failure, I will be safe.

Perfection as a survival strategy. Not as a pursuit of excellence.

And here is the distinction that changes everything: excellence is a relationship with the work. Perfectionism is a relationship with fear. Those who seek excellence rejoice in the process, tolerate error, learn from partial results, celebrate progress. Those who live in perfectionism rejoice in nothing—because any result that is not absolute is lived as a threat. Ninety percent is not victory. It is the ten that were missing. And those imaginary ten weigh more than the real ninety.

She is not trying to be the best. She is trying not to be caught. And this difference, when truly understood, breaks the heart. Because it reveals that all that extraordinary competence, all that impeccable organization, all that dedication that impresses those who see her from the outside—all of it is, in part, a shield. And whoever lives behind a shield may seem strong, may seem unshakable, may seem a reference. But at the bottom, she is tired of holding the weight. And even deeper, she longs to be able to exist without needing to protect herself.

And now, the question that matters: what does one do with this?

I will resist the temptation to give clean answers. Because clean answers, for someone living this bomb, sound like yet another demand—“now, besides everything else, I also need to heal the right way.”

What I can say is what I know about what comes before any change. And what comes before is seeing. Just seeing. Seeing the mechanism operating in real time, without trying to stop it.

Seeing that, when the manager asks about an irrelevant detail, what hurts is not the question—it is the instantaneous interpretation that “he thinks I failed.” Seeing that this interpretation is automatic, faster than thought, and that it operates before any evidence. Seeing that the body reacts before the mind: first the stomach closes, then the narrative comes.

Seeing that the concern with others, which seems generosity, is in part monitoring. Not because she is selfish—because she is afraid. And fear disguises itself as many beautiful things.

Seeing that the refusal of failure is not pride. It is terror. Terror that, if she accepts failure as a legitimate part of who she is, the entire edifice will collapse. Because the edifice was built on the premise that she must be impeccable to deserve to be where she is. And accepting imperfection seems, to this system, to accept her own demolition.

Seeing all of this. Without judgment. Without hurry to fix. Without turning observation into yet another task to be executed with excellence.

And after seeing, something perhaps no one has told her in these words:

The failures you hide are exactly the same failures everyone has. They are not bigger. They are not worse. They are not more revealing than the failures of any person sitting in the same meeting room. The difference is not in the failures—it is in the weight you give them. While others err and move on, you err and collapse inside. While others forget the missing detail, you carry it for weeks. While others distinguish between “something I did went wrong” and “I am wrong,” for you these two sentences are the same.

They are not.

And the possibility that they are not—that an error can be just an error, and not a certificate of insufficiency—this possibility, if one day it can be inhabited and not merely understood, changes everything. Not all at once. Not spectacularly. It changes slowly, in the silent repetition of moments when failure appears and, instead of the usual collapse, something different happens: a pause. A breath. And the perception, still fragile, still hesitant, that the ground did not give way. That the gaze of the other, real or imagined, did not destroy. That it is possible to fail and remain whole.

It is not that the gaze of others stops mattering. It is that it stops governing. It passes from dictator to background noise. And in the space that opens when the dictator loses the throne, something begins to happen—slowly, without a name yet, without defined form. Something that resembles the possibility of simply being. Without performance. Without proof. Without tribunal.

This is an achievement that requires freedom and responsibility, and not something that simply happens.

Freedom to see oneself whole—with extraordinary competences and with common failures. With the brilliant leader and with the woman who locks her jaw at 3 a.m. Without one canceling the other. Without one needing to be hidden for the other to exist.

Responsibility to stop outsourcing one’s own value. To not hand over to the manager, the colleague, the environment—to no one—the power to say who she is. Because none of them has sufficient information. None of them sees the whole. None of them knows what it costs to manage sixteen fronts with the dedication she puts into each one. And even if they knew, their opinion would still be their opinion—not the truth about her.

The truth about her precedes anyone else’s gaze. And that truth includes failure. Includes imperfection. Includes the day the detail slipped through and the project was not perfect and she could not deliver her best. It includes all of this—and continues to be a beautiful truth. Not despite the failures. With them.

Because life does not happen in perfection. It happens in the mess. In improvisation. In “I don’t know, but I’ll try.” In the absurd courage of waking up in the morning knowing someone may look at you with disappointment—and going anyway. Whole. Imperfect. Alive.

And if others are really looking—let them look. Let them see. Let them see everything: the competence and the fear, the organization and the chaos, the delivery and the failure. Because what they will find, if they look truly, is not the insufficient professional she imagines. It is a whole woman trying to handle a world that does not make it easy—and, most of the time, succeeding. And in the times she does not succeed, continuing.

That is not little. That is almost everything.

#ThePerfectBomb #TheGazeOfTheOther #Perfectionism #Failure #SelfKnowledge #Belief #ConsciousLeadership #Vulnerability #HealthyRelationships #HumanDevelopment #Presence #Courage #DCC #WholeLife #marcellodesouza #marcellodesouzaoficial #coachingevoce

Marcello de Souza | Coaching & Você marcellodesouza.com.br © All rights reserved

If something in this text named what you felt without being able to say it—keep going. On Marcello de Souza’s blog, there are hundreds of publications about cognitive behavioral human development, conscious leadership, and human relationships. Content for those who want to go beyond the surface. Access: www.marcellodesouza.com.br

Você pode gostar

WHY SUCCESSFUL EXECUTIVES FEAR SILENCE? (AND HOW IT SABOTAGES THEM)

25 de maio de 2025

THE INVISIBLE THEATRE OF DESIRE: WHEN YOUR RELATIONSHIPS ARE THE STAGE OF A PLAY YOU NEVER WROTE

12 de janeiro de 2026