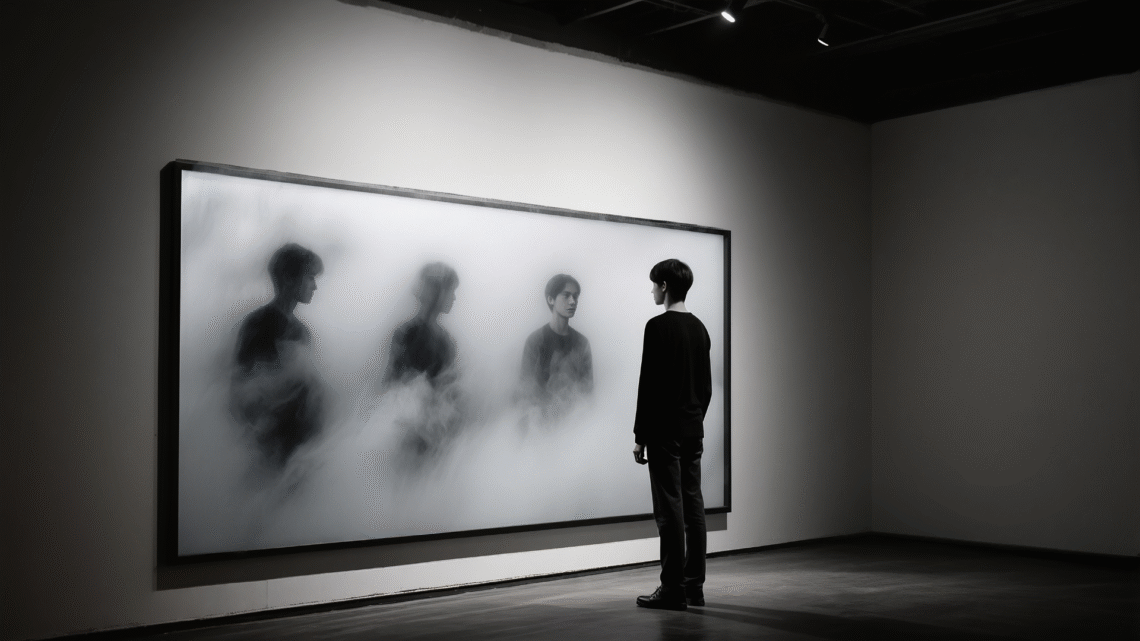

LEADERS DON’T LEAD PEOPLE. THEY LEAD GHOSTS - UNTIL THEY LEARN TO TRULY SEE

There is a seductive illusion woven into the fabric of contemporary professional relationships: the belief that we can influence others without first being pierced through by them. We live under the empire of expression — everyone wants to speak, everyone needs to be heard, everyone seeks to mark their presence through the incessant verbalisation of their truths. Yet there exists an inverse movement, silent and infinitely more potent, which is rarely acknowledged as the true matrix of human influence: the capacity to allow oneself to be inhabited by another’s reality before attempting to shape it. For herein lies a disturbing truth about the human psyche — we do not use language to express who we are; we become who we are through the language we inhabit and that inhabits us. Every word you choose does not merely describe your inner reality; it constitutes it, sculpts it, solidifies it into forms you will later call “your personality”.

When someone positions themselves in front of you in a meeting room, what truly happens in those first three seconds? It is not merely a collision of bodies or agendas. It is a confrontation between modes of existence. Between the one who arrived carrying their own urgencies and the one who manages to create an inner space empty enough to receive what has not yet been said. The difference between these two states is not technical — it is ontological. It defines who will be forgotten and who will be remembered, who will be tolerated and who will be sought out, who will be obeyed and who will be followed. Because what we call presence is not a psychological state achieved through deep breathing or body posture — it is an existential opening to the phenomenon of the other as other, not as an extension or confirmation of one’s own mental categories.

The architecture of human perception operates through layers that reveal themselves only to those who have cultivated cognitive patience. The first layer is always the loudest: words, rehearsed gestures, social masks perfectly tailored to the context. It is on this surface that most professional interactions exhaust themselves — a theatre in which everyone performs acceptable versions of themselves while the truth remains untouched, vibrating at frequencies the hurried will never reach. But there is a second layer, accessible only to those who can suspend their own internal noise: the territory of unresolved contradictions, unnamed fears, ambitions hidden behind rational discourse. It is there, in that emotional basement, that decisions truly take place.

What we call authentic leadership is not a set of competencies acquired through methodologies. It is a quality of presence that arises when someone becomes capable of simultaneously inhabiting two worlds — their own inner universe and the inner universe of the other — without confusing the boundaries between them. This capacity cannot be taught in weekend workshops. It emerges from a long and painful process of ego-emptying, of shedding what we think we already know about human beings, of abandoning those comfortable certainties that prevent us from seeing what stands before us because we have already decided in advance what should be there. And here lies the cruelest paradox of the human psyche: the more you believe you know someone, the less you actually see them. Because your prior knowledge functions as a screen that projects onto the other what you expect to find, rendering them invisible in their irreducible singularity.

There is one question that should torment every professional who aspires to positions of influence: why do some people enter a room and immediately everyone adjusts, while others go unnoticed even when they speak loudly? The answer lies not in performative charisma or verbal eloquence. It lies in something far more primitive and powerful: the capacity to make the other feel genuinely seen. And seeing, in this radical sense, does not mean approving or agreeing — it means recognising the full complexity of a human existence without reducing it to utilitarian categories.

When you observe someone with this quality of attention, something extraordinary happens in the relational field: the person senses, even unconsciously, that they stand before someone who will not judge them prematurely, who is not merely waiting for their turn to speak, who is not measuring how useful or dangerous they might be. This perception disarms defensive mechanisms built over decades. And in the space created by that disarmament, true communication finally becomes possible. Because we are, fundamentally, dialogical beings — our own identity does not pre-exist the encounter with the other; it emerges and is continuously reconstructed in the space between voices. What you call “I” is, in truth, a chorus of voices internalised since childhood, a polyphony of social discourses you have learned to orchestrate in a particular way. And when someone truly listens to you, they are not merely receiving information — they are participating in the construction of who you can become in that moment.

Yet here lies the most challenging paradox of this process: to develop this capacity for deep observation of the other, one must first turn radically inward. Most people spend their entire lives fleeing this encounter with themselves. They prefer perpetual distraction, unreflective activism, the accumulation of techniques and certifications that protect them from having to face their own dark territories. Because looking inward means confronting what we were taught to reject: our contradictions, our escape mechanisms, the unconscious patterns that govern our choices while we believe we are in control. And here resides one of the most disconcerting discoveries about the human mind: you are not who you think you are. Most of who you are happens outside the reach of your deliberate consciousness. Your most important decisions have already been made before you realise you are deciding. What you call “conscious choice” is often merely the post-hoc rationalisation of impulses that emerged from far deeper and older layers of your psychic structure.

There is a subtle violence in those who do not know themselves: such a person projects their own unresolved issues onto others, interprets behaviours through the filters of their personal traumas, reacts to ghosts from the past while believing they are responding to the present. And worse: they occupy leadership positions where their perceptual distortions affect dozens, hundreds, sometimes thousands of other lives. The contemporary organisational tragedy is not the lack of technical competence — it is the abundance of technically competent people who have never developed intimacy with their own inner landscape. Because every perception of the other is also a confession about the perceiver. When you say “that person is aggressive”, you reveal as much about them as about the categories through which you organise reality. When you claim “I can’t trust him”, you are telling a story about your own trust mechanisms as much as about the other’s trustworthiness. We never see the world as it is — we see the world as we are.

When we speak of reading people, we are not referring to body-language tricks or the mechanical decoding of facial micro-expressions. Those tools can be useful, but they belong to the realm of the surface. Reading someone, in the profound sense of the term, means capturing the invisible structure that organises that existence — the values that truly govern their choices even when they contradict their discourse, the relational patterns that repeat even when they cause suffering, the internal narratives the person tells themselves about who they are and why they do what they do. And here we reach delicate territory: those internal narratives are not original creations. They are social constructions you have internalised so deeply that you now experience them as truths about your nature. The “I” you defend so vehemently is, to a large extent, an assemblage of others’ expectations, cultural discourses, historical imperatives you have learned to call “my desires”, “my beliefs”, “my essence”. The disturbing question is: how much of you is truly yours?

And here we reach an even more delicate territory: you can only recognise in the other what you have already recognised in yourself. If you have never faced your own fear of rejection, you will be incapable of perceiving when that fear governs someone else’s decisions. If you have never investigated your own self-sabotage strategies, you will not identify when someone is unconsciously destroying what they most want to build. Our capacity to understand the other is always limited by the depth with which we know our own psychic functioning. But there is something even deeper: the unconscious does not speak only through obvious symptoms — it speaks mainly through what you CANNOT say, through pauses, slips, contradictions between verbal discourse and non-verbal communication. What you most reject in yourself does not disappear; it merely migrates to territories where you cannot see it directly, manifesting in failed acts, self-sabotage patterns, choices that seem inexplicable yet make perfect sense when understood through the logic of the unconscious.

The contemporary organisational environment is living a crisis of perception disguised as a crisis of engagement. People are not disengaged because incentives are lacking or because corporate culture is inadequate — they are disengaged because they do not feel seen. They spend their days being treated as functions, as means to ends they did not choose, as interchangeable pieces in systems that value performance but ignore existence. And then we are surprised when these same people develop cynicism, apathy, or begin seeking meaning outside work. What we forget is that the human being is not an isolated entity that later enters into relation with others — we are fundamentally constituted in the gaze of the other. You only exist as “you” because someone named you, recognised you, granted you a place in the symbolic field of human relationships. When that recognition is denied or reduced to productivity metrics, something in the most basic structure of identity begins to disintegrate.

There is an invisible economy that governs human relationships: the economy of genuine attention. And it works in the opposite way to the material economy — the more true attention you give, the more you possess. Every time you truly see someone, you create a bond that transcends transactions. You become a reference not because you have answers, but because you offer something infinitely rarer: presence. And presence, in this context, is not being physically in the same space — it is being mentally available to allow the other’s reality to transform you. Because every authentic encounter with the other is also a transformative encounter with oneself. When you truly listen to someone, when you allow yourself to be affected by what they bring, you do not leave the conversation the same. Something in you reorganises, expands, transforms. And that is precisely why most people avoid truly listening — because genuine listening is dangerous, risky, destabilising. Truly listening means accepting that your worldview may be incomplete, that your certainties may be questioned, that you may need to renounce something you considered absolute truth.

Many confuse this stance with passivity or renunciation of one’s own agenda. It is exactly the opposite. When you deeply understand what moves the people around you, when you can map their fears and desires not through logical deduction but through empathetic resonance, you acquire a form of power that does not need to impose itself by force. People naturally align with those who understand them, not out of submission but out of recognition — they have finally found someone who does not reduce them, who does not simplify them, who does not try to fit them into pre-existing categories. And here is a radical truth about the nature of human influence: you do not influence people through logical arguments or sophisticated persuasive techniques. You influence by creating a relational field where the other feels safe enough to question their own certainties. True influence does not happen when you convince someone of something — it happens when you create the conditions for that person to allow themselves to transform. And those conditions are not technical; they are existential, relational, profoundly human.

But developing this capacity requires renouncing one of the greatest seductions of modern professional life: the need to always have an answer ready. We live in a culture that confuses speed with intelligence, that rewards those who speak first rather than those who think best. And thus we create environments where everyone has instant opinions about everything, but no one has time to truly understand anything. Reflective silence has become so rare that when someone practises it, others feel uncomfortable, as if something were wrong. But silence is not the absence of communication — it is the condition for authentic communication to become possible. Because language does not transmit ready-made meanings from one mind to another; it creates meanings in the space between people. Every word you utter only gains full meaning in the specific relational context in which it emerges. The same sentence can be welcoming in one context and violent in another. Meaning is not in the words — it is in the relational field you co-construct with the other through the way you inhabit language together.

There is a form of arrogance disguised as efficiency that permeates organisational structures: the belief that we already know who the people around us are. We look at someone and immediately activate our mental categories — competent or incompetent, ally or threat, worthy of investment or disposable. This need for rapid classification protects us from the anxiety that arises when we must deal with the irreducible complexity of another human consciousness. But the price of that protection is immense: we lose access to the richness each person carries, to non-obvious possibilities, to talents that only reveal themselves when someone feels safe enough to show their less rehearsed versions. And here lies one of the most persistent illusions of the human psyche: the belief that we know others because we know their past actions. But people are not fixed entities with permanent characteristics — we are processes in constant transformation, always becoming something we are not yet fully. Yesterday’s “I” is not the same as today’s “I”, and when you treat someone as if they were an immutable essence, you freeze them into a version they may have already outgrown. You are not seeing who they are — you are seeing who you decided they should be.

When you develop the ability to observe without premature judgment, something remarkable happens: you begin to perceive patterns that were previously invisible. You realise that the person who is aggressive in meetings is actually terrified of being considered incompetent. You notice that the colleague who always agrees is in reality consumed by unexpressed resentment. You see that the authoritarian leader is desperately trying to hide their own insecurity behind masks of certainty. And with these perceptions, your responses become radically different — you stop reacting to symptoms and start addressing causes. But something crucial must be said: these perceptions only become possible when you have renounced the need to always be right. Because seeing the other clearly requires first giving up your defensive interpretations, those readings that protect your ego but distort reality. Every time you catch yourself thinking “this person is like this because they want to harm me”, stop and ask: what in me needs this narrative? What discomfort am I avoiding by turning the other’s behaviour into malicious intent? Often, what you interpret as a personal attack has nothing to do with you — it is the manifestation of the other’s unprocessed pain, of anxiety they cannot name, of fear that governs their choices without their own awareness.

There is one question we rarely ask ourselves: what does it really mean to know someone? We are not talking about knowing biographical facts or superficial preferences. We are talking about understanding the emotional architecture that sustains that life — the events that shaped their way of trusting or distrusting, the wounds that still pulse behind apparently inexplicable behaviours, the dreams that were abandoned and now manifest as bitterness or resignation. This kind of knowledge is not acquired through questionnaires or group dynamics. It emerges only when you are willing to invest real time, sustained attention, genuine curiosity. Because knowing someone is participating in the creation of who that person is becoming. Every human relationship is a process of co-authorship — you do not discover the other as if they were a fixed object waiting to be revealed; you co-create the other through the quality of your presence, the questions you ask, the space you offer. There is no “truth” about someone independent of the relationship in which that person manifests. You are different with each person you meet because each relationship summons distinct dimensions of your being. The “you” that emerges with your boss is not the same “you” that emerges with your best friend. Not because you are false, but because identity is always relational, always contextual, always being negotiated in the field between people.

The contemporary professional world has trained us to be efficient, but not profound. To deliver quick results, but not to build lasting understandings. To adapt to external demands, but not to cultivate inner wisdom. And so we find ourselves in a paradox: the more communication techniques we learn, the less we truly connect. The more influence strategies we master, the less authentic influence we exert. Because true influence does not come from techniques — it comes from perceptual integrity. And perceptual integrity is only possible when you recognise that every relationship is a shared construction of reality. There is no objective reality “out there” that you simply perceive neutrally. All perception is interpretation, all interpretation is traversed by your personal history, your fears, your unrecognised desires. What you see in the other says as much about you as about them. And when you finally understand this, you stop fighting reality and begin negotiating with it in a more sophisticated, conscious, responsible way.

Perceptual integrity means that what you see in the other is not contaminated by what you need to see in order to confirm your own narratives. It means you can distinguish between your projections and the independent reality of that person. It means you have developed sophisticated enough internal filters to separate automatic judgments from hard-won understandings. And this conquest is not a single event — it is daily, moment-to-moment work of disidentifying with your own mental processes in order to see what is truly happening. Because here is a brutal truth about the human psyche: you are not in control of your thoughts in the way you imagine. Most of what you think was not consciously chosen — it emerged from automatic interpretive structures installed in you long before you could question them. Your parents, your culture, your traumatic experiences, the social discourses you absorbed — all of this created lenses through which you see the world. And those lenses are so transparent to you that you believe you are seeing reality “as it really is”, when in fact you are seeing only a specific, constructed, limited version. Developing perceptual integrity is learning to see your own lenses, to recognise your own filters, to question your most fundamental certainties.

Here perhaps lies the most disturbing insight of this text: most people do not want to be truly seen. They want to be recognised for the masks they have so carefully constructed. They want validation for their social personas, not for their hidden truths. And when someone with refined perception appears, these people often recoil, disturbed by the feeling that their disguises have been penetrated. That is why deep observation must be accompanied by delicacy — you must respect others’ defences even when you can see through them. Because those defences are not whims or falseness; they are psychic survival structures built over decades, often in response to real wounds. When you prematurely disarm someone’s defences, you may cause more harm than good. The art lies in creating a space safe enough for the person to lower their own defences voluntarily, at their own pace, in their own time. You cannot force anyone into authenticity — you can only create the conditions in which authenticity becomes a less terrifying possibility.

What we call charisma is, to a large extent, the capacity to make the other feel interesting to themselves. When you pay genuine attention to someone, when you ask questions that reveal real curiosity and not mere social politeness, when you show you are willing to be surprised by what the person has to say, you activate a more expansive version of themselves. People remember how you made them feel — and nothing makes someone feel better than being genuinely perceived. But beware: this is not a manipulation technique. If you fake interest, if your questions are strategies to obtain information rather than authentic invitations to dialogue, people notice. Perhaps not consciously, but on some intuitive level they sense the difference between being studied and being met. Because the human relational field operates through subtle frequencies that escape deliberate consciousness yet profoundly affect the quality of connection. You know when someone is truly present and when they are merely executing a social protocol. That perception does not happen through rational analysis — it happens through bodily, emotional, energetic resonance.

But we always return to the same starting point: you cannot offer others what you have not cultivated in yourself. If your own inner life is unexplored territory, if you systematically flee from confronting your own shadows, if your emotions are uninvestigated mysteries, then your capacity to understand others will always remain superficial. You may learn techniques, memorise frameworks, accumulate certifications — but you will never access the deepest dimension of relational intelligence, the one that emerges from resonance between two complexities that recognise each other. And here is the final paradox: the more you know yourself, the more you realise how much you do not know yourself. Self-knowledge is not a destination where you finally understand who you are once and for all. It is an endless process of discovering ever-deeper layers, ever-subtler contradictions, dimensions of your being you never suspected existed. Every answer you find about yourself generates ten new questions. And that is the only way to remain psychologically alive — to stay curious about yourself, to remain willing to be surprised by what you may still discover in the unexplored territories of your own psyche.

The organisational transformation so many seek will not come from new methodologies or hierarchical restructurings. It will come when enough people within those structures develop the quality of presence we have been describing. When leaders stop managing human resources and start witnessing human existences. When colleagues stop competing for recognition and start collaborating from mutual understanding. When organisational culture is built not on values declared on walls, but on daily practices of genuine attention. Because organisations are not abstract structures — they are networks of human relationships. And the quality of those relationships determines everything: the capacity to innovate, the speed of adaptation, resilience in crises, talent retention. You can have the best processes in the world, but if people do not trust one another, if they do not feel seen and valued, if they must expend energy protecting themselves from internal threats instead of focusing on external challenges, your organisation will never reach its potential. And building that quality of trust does not happen through team-building dynamics or motivational speeches. It happens through thousands of daily micro-interactions in which people choose to truly see each other or to hide behind professional masks.

And here we arrive at the most radical invitation: what if the most important professional development you can undertake is not an MBA or a leadership course, but a merciless dive into your own psychic functioning? What if the most sustainable competitive advantage is not mastering new technologies, but mastering your own mind? What if the most strategic investment is developing the capacity to be entirely present, free from the internal distractions that keep us always halfway from where we are? Because being present is not a passive state of relaxation — it is the most active and demanding capacity that exists. Being truly present requires continuously renouncing the temptation to escape into thoughts about the past or fantasies about the future. It requires facing the discomfort of not knowing what will happen in the next three seconds. It requires abandoning your pre-fabricated scripts and allowing yourself to be affected by what is emerging right now, in this unique and unrepeatable moment. Most people live on autopilot, responding to present situations with patterns from the past, never really here, always divided between memories and projections. And then they wonder why their relationships feel superficial, why they cannot connect genuinely, why they always feel they are performing a role instead of simply existing.

The answer to these questions does not fit into competency lists or professional maturity models. It calls for a silent revolution in how we conceive success, influence, and fulfilment. It demands that we recognise that the quality of our perception determines the quality of our relationships, and that the quality of our relationships determines the quality of our professional and personal existence. There is no shortcut. There is no technique that can replace the work of becoming profoundly conscious — of oneself first, and then, finally, of others. And conscious, in this context, does not mean merely having information about oneself. It means inhabiting your own being with a quality of attention that reveals dimensions that remained invisible. It means developing the courage to see your own contradictions without needing to resolve them immediately, to recognise your own fears without being governed by them, to accept your own limitations without using them as an excuse not to grow. It means, finally, understanding that you are not a fixed entity struggling to remain stable in a changing world — you are a process in constant transformation, and the more you resist this truth, the more suffering you create for yourself and for everyone around you.

#marcellodesouza #marcellodesouzaoficial #coachingevoce #relationalintelligence #organizationalconsciousness #authenticleadership #humanperception #professionaltransformation #humandevelopment #organizationalpsychology #consciousrelationships #organizationalculture #authenticpresence #humanizedmanagement #humanbehavior

Do you want to deepen your understanding of human cognitive-behavioral development, conscious relationships, and organisational transformation? Visit my blog, www.marcellodesouza.com.br, where I keep hundreds of publications exploring the deepest dimensions of human behavior and evolutionary relationships in personal and organisational contexts. Go to www.coachingevoce.com.br and discover content that goes far beyond the conventional.

Você pode gostar

YOU DIDN’T GET WHERE YOU ARE TO REMAIN WHO YOU’VE ALWAYS BEEN

5 de janeiro de 2026

THE ILLUSION OF STRATEGIC PRESENCE

6 de janeiro de 2026